Exploring Global Commodities: How I Found a Way to Engage Undergrads through 3D Scanning

Matt Coler from the University of Groningen shows how he brought 3D scanning into his "Local Cultures / Global Commodities" course. Using KIRI Engine, he found an engaging way to connect students with global commodities through tech and hands-on learning.

Associate professor Matt Coler from the University of Groningen shared his story behind planning the undergraduate course "Local Cultures / Global Commodities" using the KIRI Engine and 3D scanning technologies.

Introduction

My name is Matt Coler, I’m an Associate Professor of Language & Technology at the University of Groningen’s newest faculty, Campus Fryslân. My scientific background is interdisciplinary -I did my Ph.D. research in the field of linguistic anthropology, working with indigenous communities in the remote regions of the Andes. After a postdoc position, I took the unusual step of joining an AI start-up as a department head of the “Cognitive Technologies” group. I was interested in exploring how insights from social sciences could support innovations in AI. But I missed teaching and the “blue sky research” possible at university -and with the new faculty opening up, it seemed like the best of both worlds, part start-up part university. I think of myself an “intrapreneur” because I like to develop new opportunities within an organization. For example, my team and I launched the only graduate program dedicated exclusively to voice technology. I also spearheaded an independent research line dedicated to technological innovations in teaching “EDU+”, which is how I came across the KIRI Engine.

Q: What were the problems you were trying to solve in your class, and what method did you try?

A: First some background into the course: I am currently teaching an undergraduate course called “Local Cultures / Global Commodities” which is dedicated to understanding the material world around us from an anthropological perspective. In this course, students reflect on articles about global commodities written from a local, ethnographic perspective. This means that after taking this course, students no longer see, for example, a pair of gold earrings as simply a pair of gold earrings -but as a product developed from a commodity that was extracted from a mine in rural Africa. Along the way, the gold passed through the hands of a miner, a purchaser, a jewelry company, a distribution company, and a store clerk. In this class we want to shine a light on the people and cultures who are ordinarily invisible in such commodity chains, so we examine the lives of gold miners, in this case, in Africa, Mongolia, and Scandinavia, and the interplay with issues like cultural and linguistic diversity, sustainability and more. We do this for an array of commodities.

The million-dollar question is how to connect to the students in such a way that they actively engage with the content. While reading articles and books is absolutely critical, I also wanted to help the students be more than passive recipients of content. That is, I wanted to find a way for them to become active generators of knowledge and reflection. Doing this at the undergraduate level is no easy thing. I tried engaging students with online forums where they had to share their questions and answers. I also tried assigning video projects, where students would provide a video response to something they read. Neither of these worked as I wanted.

Q: So after you made several attempts, what inspired you to investigate the use of 3D scanning?

A: With that puzzle in mind, I started to think about new approaches to classroom engagement. I knew I needed something cutting-edge which could help me inspire students to reflect on course content and inspire a sense of curiosity about the intellectual and societal challenges of the field. At first, I thought of inviting students to photograph commodities and write an accompanying essay, but I decided that this would not capture the students any more than the forum and video assignments would. So what else could I do?

3D scanning seemed like a natural fit. Students could scan commodities easily from their smartphones and reflect on course content individually and in small groups. Plus, scanning removes a 3D object from its environment -I think that invokes a fresh perspective that a photograph does not. Somehow, even ordinary objects once rendered in 3D become a new kind of digital artifact that invokes new questions. This matched perfectly with the motto of the class, which is “making the familiar strange and the strange familiar”.

I imagined the possibility of, say, scanning something as ordinary as a Big Mac and reflecting on where the individual components of it came from. What was the life like of the cattle hands who raised the beef? Where is the flour in the bun coming from? Who picked the lettuce and tomato? With such exercises, students could see their own world a little differently. And by sharing their scans with others, they could also learn about each other in a new way. These outcomes matched what I feel like academia is about.

Together with Spyretta Leivaditi and Angelos Konstantinidis, we grew this concept into a larger educational project and applied for funding from the Dutch Ministry of Culture, Education and Science for a Virtual Exchange Grant. Once awarded, we began a collaboration with Prof. Derek Lackaff and Prof. Kristin Lange at Elon University (North Carolina, USA) who teach a similar course in the US. Now students on both sides of the Atlantic use the KIRI Engine to scan ordinary objects, reflect on their origins, and share them in a virtual international exchange.

Q: This is very cool to know! But what made you choose the KIRI Engine over other alternatives?

A: Spyretta and I downloaded other 3D scanner apps onto our phones and tested them across platforms. It was time-consuming work!

We evaluated them according to specific criteria: We wanted students to be able to make 3D scans that would look good on all devices, from the cheapest Android and the newest iPhone. We also wanted to find software that would do what we need without much of a learning curve, and, critically, for free. KIRI Engine checked all the boxes. Also, the instructional gifs made it easy to try out right away.

When we compared KIRI Engine scans with that of others, the results stood out, not just for ease of use but for the quality of the results. Other features like the ability to share with a URL were also appealing.

But let me put it simply: When I found myself scanning for fun at home, outside, during coffee breaks, over breakfast, and on my commute, I knew it was going to be a hit!

Q: Haha, yeah 3D scanning can be addictive sometimes. Did your students find it fun as well?

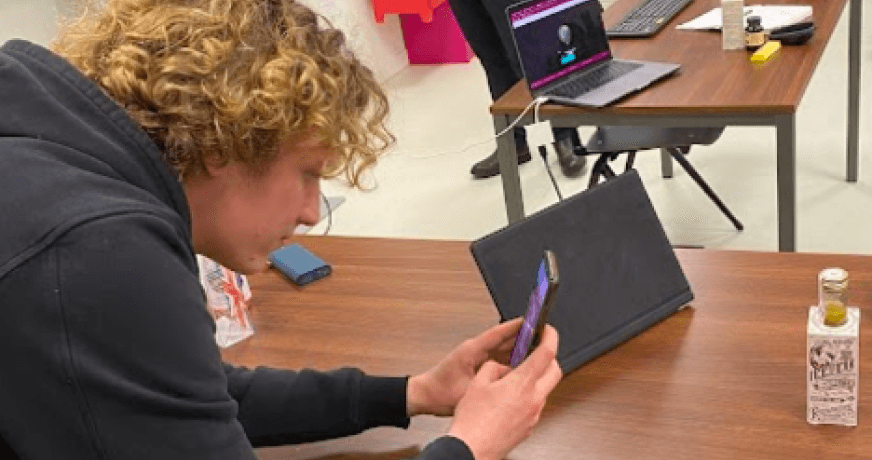

A: The students were very enthusiastic to have a reason to pick up their phones and try different approaches to scanning. People emptied out their bags to look for new things to scan. Some students even brought things from home, including even a red pepper. I didn’t expect them to enjoy it as much as they did. And even after the lecture, students were comparing scans in the halls. It was a hit!

Q: Could you share with us some of your future plans?

Well, the first thing is to see how this approach works. If it helps the students learn and engage as we expect it to, then the next step is to disseminate this approach to other instructors teaching similar courses. I would also like to co-author a paper outlining what we achieved in a journal of educational practices.

As for this particular course, I would like to investigate how 3D scans can be put into a virtual environment and visited by the students. I envision a gallery of ordinary objects, with thematic exhibits where objects are grouped by their origins or cultural meanings. This could then grow every year, as students contribute to it.

A wild idea: Aside from scanning commodities, I also thought it may be interesting to scan trash. Yes, this may sound strange at first -but in this course, students reflect on “de-commodification” and their own role in the commodity chain. By actually looking at trash not as “refuse” but as a digital artifact we can see this from a new perspective.

Overall, I want to continue to pursue new multimedia approaches to teaching that engage this generation of students without compromising academic rigor and quality. 3D scanning could have a large role to play there.